After years of growth, the future of California’s charter sector is in doubt.

With the passage of Assembly Bill 1505, which places numerous restrictions on the expansion and operation of charter schools in the Golden State, opponents of charters have claimed their biggest prize since the 2016 election when President Donald Trump’s education secretary, Betsy DeVos, replaced former President Barack Obama as the public face of the charter movement.

For Democrats like us, who believe in low-income students’ right to a better education, this is a depressing state of affairs. After all, dozens of studies have found that black and Latino students in charter schools make substantially more academic progress than those in traditional public schools — especially in major cities like Los Angeles. And a growing body of research suggests that achievement in district-run schools increases in response to charter competition — contrary to the assertions of charter opponents.

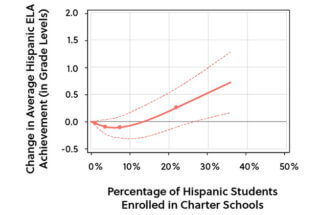

Logically, those two strands of research imply that an increase in the percentage of students who attend charter schools should lead to systemic gains — that is, to an overall increase in achievement. So to test that hypothesis, in a recently published study, we analyzed the relationship between the rise in “charter market share” in hundreds of school districts across the country and the average reading and math achievement of all publicly enrolled students in those districts — including those in traditional public schools.

The results were instructive. In general, greater charter market share is associated with significant achievement gains in reading, as well as modest gains in math. However, when the data are broken down by race, it’s clear that these gains are highly concentrated among black and Latino students. For example, for Latino students in the country’s 21 largest cities — places like Detroit, Philadelphia, and yes, Los Angeles — our estimates suggest moving from a zero percent charter market share (meaning charter schools enroll no Latino students) to a 35 percent share (meaning charter schools enroll 35 percent of all Latino students in the area) boosts the reading and math achievement of the average Latino student approximately half a grade level. And the same is true of black students.

By the standards of the field, these are monumental gains — the kind many progressives say they hope to achieve. Yet at this point, they should come as no surprise. The evidence that charter schools have benefits for students of color is now so unambiguous that denying it is a bit like denying the science of climate change (which a growing majority of Republicans now accept). And of course, the stakes of the charter school debate are also extremely high, especially for the families who are directly affected.

Between 2009 and 2015, the percentage of black students in Los Angeles who enrolled in a charter school increased from 19 percent to 27 percent, and the percentage of Hispanic students increased from 8 to 17 percent. Yet in recent years, the growth in charter enrollment has slowed significantly, with the charter market share for all L.A. students only moving from 23 percent to 26 percent between 2015-2018. And the passage of Assembly Bill 1505 and the unions’ ceaseless attempts to paint California charters (all of which are run by non-profit organizations) as corporate boogeymen, the risk that it will grind to a halt has never been higher.

Like any disruptive policy, charter schools provide plenty of grounds for legitimate debate. But that debate should be focused on how they can fulfill their potential, not on how much change the public education system can handle or how many black and Latino students should have the chance to learn a little faster and more successfully.

Simply put, a de facto moratorium on new charter schools, which is what the governor just signed, would be devastating for Los Angeles students. That’s why it’s critical that more community-minded Democrats acknowledge the evidence on charter schools — as we acknowledge the science of climate change — and vote accordingly.

David Griffith is a senior research and policy associate for the Thomas B. Fordham Institute and the author of a new report: “Rising Tide: Charter School Market Share and Student Achievement.”

Caprice Young is national superintendent at Learn4Life Schools, a charter school network serving 40,000 students across 80 learning centers in California, Ohio, and Michigan. She served on the Los Angeles Unified School District school board from 1999 to 2003 and is a member of the Fordham Institute Board of Trustees.